This project was made possible by the very generous support of an anonymous donor and

Pulling together a project of this size takes a lot of work. The help of Jayme Nelson, Katherine Hill and Kathryn Wagner from Inside Education was invaluable. We couldn’t have done it without you. Thank you!

AC Atienza, Brendan Bate, Shannon Smithwick, Steff Stephansson, Kaleigh Watson, Andrew Wilson.

Invasive species represent a significant ecological challenge, intertwining complex issues of biodiversity loss, ecosystem disruption, and impacts on human activities.

An invasive species is an organism that is not native to the location it is living in, and has a tendency to spread, causing harm to the environment, human health, or the economy. Thriving beyond their natural habitats, these species can disrupt local ecosystems and outcompete native organisms for resources [1].

The introduction of invasive species to new areas is often helped by human activities. Whether accidentally, through global shipping or not cleaning equipment such as watercraft and fishing gear, or intentionally, through trading or horticulture, these species find new territories without their natural predators [2]. It is important to note that invasive species also include those native to parts of Canada that have been introduced or expanded into areas outside their historical range [3].

Invasive species are often viewed negatively, but it’s important to remember that species moving into new areas is a natural process. However, a problem arises when humans speed up this process, introducing many species to new places quickly. This can lead to environments becoming too similar worldwide and might even cause some ecosystems to fail in ways we’ve never seen before [4].

Other words for ‘invasive’ species can be ‘non-native’, ‘non-indigenous’, ‘alien’, ‘introduced’ or ‘exotic’ [5].

Once established, invasive species can swiftly outcompete native flora and fauna, leading to decreased biodiversity [6]. They can also introduce diseases, modify habitats, and disrupt food webs. Their economic impact can be profound, affecting agriculture, fisheries, and forestry, with costs running into billions annually for management and lost revenue [7]. Aquatic invasive species are notorious for altering water quality and habitat conditions, posing threats to both native species and human health.

Rapid introductions of species by humans can cause ecosystem homogenization or uniqueness, and potential collapse, yet it’s crucial to balance the dialogue on invasive species. Understanding the historical context of native versus non-native species and focusing on the specific ecological impacts of invasive species can lead to effective conservation strategies [8].

Invasive species threaten diversity in our planet’s ecosystems. Aquatic invasive species impact our aquatic resources by reducing biodiversity and habitat quality, outcompeting native species, challenging aquatic industries, harming recreational activity, and permanently altering ecosystems [9].

Some invasive species use water more efficiently than native species, or require more water to thrive. For example, certain types of invasive plants, such as Phragmites (a type of reed) or Tamarisk (also known as salt cedar), consume large amounts of water [10]. When these species establish themselves along riverbanks or in wetlands, they can reduce the amount of water available in these ecosystems by absorbing more water from the soil and groundwater than native plants. This increased consumption can lead to lower water levels in streams, rivers, and lakes, contributing to water scarcity.

Invasive species can alter the structure of water bodies and their natural flow. Aquatic plants like Hydrilla or Eurasian watermilfoil can grow rapidly, forming thick mats that cover water surfaces [11]. These mats can impede water flow, leading to increased evaporation and decreased water availability downstream. This alteration of water flow and sediment affect the recharge of aquifers, further impacting water availability.

Invasive species can degrade water quality, which indirectly contributes to water scarcity by limiting ‘usable’ water resources. For example, the decay of plant material from invasive species can deplete oxygen levels in water bodies, causing dead zones where fish and other aquatic life cannot survive [12]. This process, known as eutrophication, requires water treatment to make the water suitable for human consumption and agricultural use, thus reducing the effective supply of water.

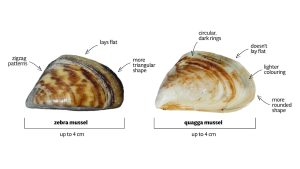

Some invasive species can introduce or concentrate pollutants within ecosystems. For example, certain invasive mussels, like zebra and quagga mussels, filter and accumulate toxins and pollutants from the water, which can then be passed up the food chain, impacting wildlife and potentially human health [13]. Their ability to bioaccumulate pollutants can turn them into vectors for water contamination.

Invasive species compete with native species for essential resources like food, water, and habitat space. Because invasive species can sometimes be more aggressive or efficient in resource use, or lack local natural predators, native species may be outcompeted [14]. This competition can lead to the decline or extinction of native species (e.g. ash trees from the emerald ash borer [15]), especially those which are already vulnerable or endangered.

Invasive species can introduce new diseases and parasites to native species that have no immunity or defence [16]. These diseases can destroy native populations, further reducing biodiversity.

Invasive species can hybridize with closely related native species, leading to genetic pollution. This hybridization can dilute the genetic distinctiveness of native species, potentially reducing their viability and adaptability to changing environmental conditions [17]. Over time, this can lead to a loss of biodiversity as unique genetic lineages are lost.

The unchecked growth of invasive species can harm crops, fisheries, and forests, directly affecting industries relying on these resources. In aquatic environments, invasive species like zebra mussels can clog water intake pipes, affecting water treatment and power plants, which can lead to expensive maintenance and repairs [18]. Invasive species can harm native wildlife and plants, affecting tourism and outdoor recreation industries. Overall, the management, control, and eradication of invasive species can require significant financial investment, adding to the economic burden they impose on communities.

Aquatic invasive species bring significant economic costs, impacting essential services and industries. They clog water lines leading to dams, power stations, wastewater treatment plants, and drinking water facilities, causing blockages that require costly cleaning and increasing operational expenses [19]. These species also foul aquaculture operations, like shellfish, necessitating expensive control, monitoring, and eradication measures [20]. Businesses dependent on natural water bodies, such as tourism, fisheries, and aquaculture, face decreased revenue due to these invasive species. Recreational activities, including fishing, swimming, boating, and tourism, suffer as these species damage infrastructure, make waters unsuitable for various activities, and displace native species crucial for recreational fishing.

Canada faces challenges from invasive species that threaten its waterways ranging from affecting the health of ecosystems to impacting the economy and recreational activities. Here are some Canada-specific examples of water-related invasive species:

Zebra and quagga mussels are small, live in freshwater, and can quickly colonize lakes and rivers. Originating from Eastern Europe, these mussels were first discovered in the Great Lakes in the 1980s [21]. They filter plankton from the water, which can disrupt local food webs and harm native species. Additionally, they clog water intake pipes, affecting municipal water supply systems, power plants, and irrigation infrastructure, leading to high maintenance costs.

European watermilfoil is an invasive aquatic plant that forms dense mats on the surfaces of water bodies, hindering recreational activities such as swimming and boating. It can also outcompete native aquatic plants, alter habitats for fish and other wildlife, and reduce biodiversity [22]. Once established, it is extremely difficult to eradicate and spreads quickly when carried by boats to new locations.

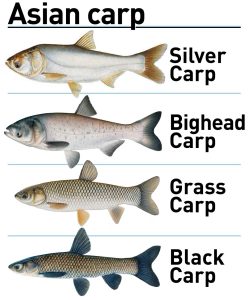

Asian carp is a collective term for species such as bighead, silver, grass, and black carp [23]. These fish are highly adaptable and fast-growing , posing a significant threat to the Great Lakes and other Canadian waters. They compete with native fish for food and habitat, leading to the decline of native species. The presence of Asian carp in Canadian waters could severely impact commercial and recreational fishing industries [24].

The round goby is a small, bottom-dwelling fish first discovered in the Great Lakes in the 1990s, likely introduced through ballast water from ships [25]. Round gobies eat the eggs and young of native fish and compete with them for food and habitat. They are also a nuisance for anglers, as they can dominate bait traps and hooks intended for other species [26].

The Government of Canada uses 4 pillars to approach aquatic invasive species management [27].

Community awareness of aquatic invasive species is vital since they are the first line of defence in preventing the introduction and spread of new species. Knowledge about how invasive species relocate and the potential harm they can cause enables individuals to take proactive measures, such as thoroughly cleaning boats and equipment.

Additionally, early detection by vigilant community members can prompt quick management actions to eradicate an invasive species before it becomes established. Community engagement is crucial for the protection of local ecosystems, which face threats from reduced biodiversity, altered habitats, and the endangerment of native species due to invasions. Beyond environmental concerns, aquatic invasive species can inflict substantial economic damage, impacting water infrastructure, fisheries, tourism, and recreational activities. The economic health of communities often depends on the vitality of these sectors, underscoring the importance of community support for control measures. Some invasive species present direct threats to public health by carrying diseases or creating unsafe conditions in water bodies.

These questions aim to encourage students to think critically about invasive species’ impact on ecosystems, economies, and societies.

Organize a field trip to a local natural area or park. Prior to the visit, have students research invasive species known in the area. During the field trip, students can identify invasive species, document their findings with photographs, and note how these species interact with their surroundings. Perhaps frist chat to your municipality’s gardeners about where they are battling invasive species and then visit those areas.

Divide students into groups and assign each group a position on various management strategies (e.g., mechanical removal, chemical treatment, biological control). Students research their assigned strategy, prepare arguments, and debate its merits and drawbacks in class.

Students are assigned roles as various stakeholders (e.g., farmers, conservationists, government officials) in a scenario involving invasive species and their impact on ecosystem services. They must discuss and propose solutions to manage the invasive species, considering the needs and concerns of their stakeholder group.

Students create a fictional invasive species, considering factors such as adaptations, spread mechanisms, and potential impacts on ecosystems. They illustrate their species and present it to the class, explaining how it would fit into and potentially alter its new environment.

Using digital tools or physical maps, students can create a map showing the spread of a particular invasive species over time in their region or country. They can research the history of the species’ introduction, its spread, and its ecological and economic impacts.

Collaborate with a local environmental organization to participate in an invasive species removal effort. Students learn about the species they are removing, the reasons for its management, and safe removal techniques.

Share this Post:

We provide Canadian educational resources on water practices to promote conservation and sustainability. Our team crafts current and relevant content, while encouraging feedback and engagement.

The Canada WaterPortal is a registered charity, #807121876RR0001

We recognize and respect the sovereignty of the Indigenous Peoples and communities on whose land our work takes place.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved.