This project was made possible by the very generous support of an anonymous donor and

Pulling together a project of this size takes a lot of work. The help of Jayme Nelson, Katherine Hill and Kathryn Wagner from Inside Education was invaluable. We couldn’t have done it without you. Thank you!

AC Atienza, Brendan Bate, Shannon Smithwick, Steff Stephansson, Kaleigh Watson, Andrew Wilson.

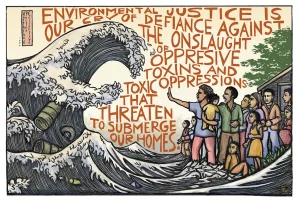

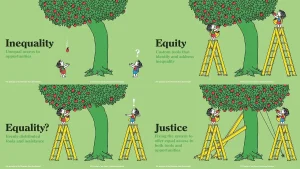

Social equity refers to the fair and equitable distribution of environmental benefits and burdens across all members of society, regardless of their background, race, gender, or economic status [1]. It emphasizes the need for all individuals to have equal access to resources, opportunities, and rights, aiming to eliminate disparities and injustices in society.

When we talk about social equity and the environment, we’re looking at how environmental policies, practices, and changes impact different communities in various ways. Not everyone experiences environmental benefits (like clean air and water, green spaces, and healthy ecosystems) or burdens (such as pollution, natural disasters, and the effects of climate change) equally [2].

Imagine two neighbourhoods: one is a wealthy area with lots of green spaces, trees, and access to clean water; the other is a less wealthy area, with few parks, industrial facilities nearby, and poorer water quality. Despite living in the same city, residents in these neighbourhoods have very different access to clean air, water, and recreational spaces. This disparity is a simple example of a lack of social equity in their environments.

The fairness in how environmental benefits and burdens are distributed within society matters because it directly affects health and quality of life. When certain groups bear the brunt of environmental negatives (like pollution or lack of access to clean water) while others enjoy more of its positives, it leads to social and health inequities.

Equity-seeking communities often suffer more significantly when environmental changes such as altered hydrological cycles, reduced water quality, disruption of aquatic habitats, deforestation, changes in precipitation patterns, and increased runoff and erosion occur. These impacts can compound with existing vulnerabilities, including limited access to resources, infrastructure, and political power to advocate for change.

Examples of how environmental changes can affect equity-seeking communities:

Changes in how water moves through nature can cause less water to be available or make it harder to predict when and where it will rain or snow or melt. This can affect drinking water, farming, and keeping clean. Communities that depend on natural water sources might not have enough, which can hurt their health and food supply [3].

Pollution and reduced water quality can create serious health problems for people who depend on rivers, lakes, and groundwater for drinking, cooking, and bathing. Without proper water treatment facilities, these communities are at risk of getting sick from waterborne diseases [4].

Damage to rivers, lakes, and other water bodies affects fish populations and biodiversity. This can hurt communities that reply on fishing for food and jobs. With fewer aquatic species and other resources, people may struggle to eat and earn money [5].

Forests are a source of medicinal plants, food, and resources for communities. Cutting down forests and not replanting them leads to the loss of these resources, including a sustainable source of wood for communities that rely on them for food and work. Forests also provide ecosystem services, which are the direct and indirect benefits that ecology provides humans [6], such as keeping the soil in place and water regulation. If the forests are gone, those added benefits are also gone, and communities can face more problems from changes in their environment [7].

Water scarcity, or “water shortage”, is a global issue that extends across national boundaries and requires international cooperation. In fact, globally, 2 billion people or one-quarter of the world’s people do not have access to safe drinking water in their homes [8]. Social equity emphasizes the importance of wealthier nations supporting less wealthy countries in developing water infrastructure and sharing technological information to help manage water resources effectively and equitably.

Clean water lets people bathe, handle waste, clean, and cook safely without the risk of getting sick or the impacts of poor hygiene. Nearly half of the world’s population – 46% – do not have access to safely managed sanitation [9]. Cleaning up and preventing water pollution is important for public health, as waterborne diseases are more prevalent in areas with poor water quality.

Ensuring everyone has access to clean water is not just about treating and preventing pollution. It is also about building and maintaining the infrastructure needed to deliver safe water and sanitation services to every community, while making sure they last over time, regardless of the community’s socioeconomic status.

The effects of these environmental changes on poor communities demonstrates the need for integrated, equitable approaches to environmental management and development. To help these vulnerable communities, policies are needed that help provide resilience to affected communities. This involves improving access to clean water, supporting sustainable agriculture, and reducing disaster risk, within the framework of social equity and environmental justice.

In Canada, water-related social equity concerns highlight the discrepancies in access to clean and safe water, the impacts of industrial activities on water resources, and the involvement of communities in managing and governing their own water resources. Some specific examples include:

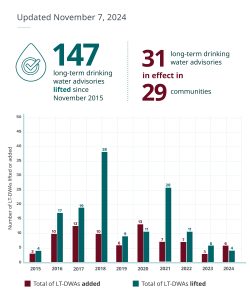

Many Indigenous communities in Canada have been under long-term boil water advisories. Despite Canada having the world’s third-largest freshwater reserves, 30 long- term drinking water advisories remain active on public systems on reserves [10].

Remote and northern communities in Canada often face challenges in accessing reliable and safe water sources. Because of their geography, it can be difficult to find local water sources, or to build appropriate water treatment plants. Hiring and training local operators, maintaining infrastructure, and the high costs associated with remote communities results in an imbalance in water quality and access that are not faced by less remote and southern communities [11].

In regions with significant industrial activity (click here to learn more about water and industry), such as Alberta’s oil sands, water contamination from chemicals and waste can lead to pollution of rivers and groundwater, affecting both the environment and the health of nearby residents [12].

Climate change is likely to worsen water scarcity in British Columbia and the Prairies, specifically due to changing precipitation patterns affecting agriculture, hydropower, and community water supplies (click here to learn about drought). The uneven distribution of these impacts raises questions about social equity, as some communities are less equipped to adapt to these changes [13].

Overcoming inequity requires commitment from everyone involved—governments, businesses, non-profits, and community members. Here are several ways that communities can contribute to reducing inequities:

Communities can organize local water monitoring initiatives to track water quality and quantity. This grassroots approach empowers residents to collect data, identify pollution sources, and understand seasonal variations. By monitoring their water resources, communities can advocate for better water management practices based on concrete evidence.

Water management policies and regulations are often made at provincial, territorial, or federal levels. Involving community members in water governance adds local voices, concerns, and ideas to decision-making processes. This can be achieved through the formation of water user associations, community advisory boards, or local watershed management councils. Inclusive governance, which is the idea of including all members of a community, helps ensure that policies and projects do not disproportionately impact vulnerable populations.

Communities can advocate to governmental bodies for policies that address water-related social equity concerns, like investments in infrastructure to ensure all have access to clean, affordable water. Collaboration with non-governmental organizations, academic institutions, and government agencies can amplify their voice and impact, pushing for systemic changes that address the root causes of inequity.

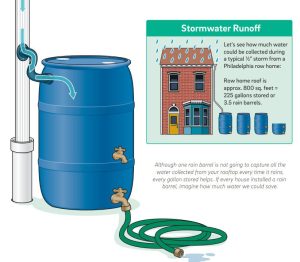

Communities can implement rainwater harvesting systems and greywater recycling, especially in areas facing water scarcity or quality issues. These systems are an alternative source of water for non-potable uses, reducing the demand on municipal systems and helping to alleviate water stress.

The underlying concept of “no net loss” is that any development in a community should, at a minimum, not result in a net (or overall reduction) in the availability of something to that community. In the context of water, the concept means that that any water consumed in the development needs to be replaced.

A practical application of this concept is often seen in the context of wetlands. Wetlands, for various reasons, have sadly often been destroyed and replaced by new development such as subdivisions. More recent approaches (e.g. City of Calgary’s wetland policy [14], Government of Quebec [15], Government of British Columbia [16]) are to protect (preferable) or replace wetlands and so preserve the many benefits offered by those wetlands.

Indigenous and local knowledge systems offer valuable insights into sustainable water management practices that have been refined over generations. Recognizing and integrating this knowledge into broader water management practices can contribute to more resilient and equitable water systems.

By engaging in these activities, communities can begin to address immediate water-related social equity concerns and invest in the long-term sustainability and resilience of their water resources. Community-driven initiatives ensure that solutions are locally relevant, culturally appropriate, and sustainable, marking a significant step toward addressing global water equity challenges.

The following learning opportunities provide students with a comprehensive understanding of social equity in the context of environmental issues, encouraging them to become informed and active participants in their communities.

Equity and Resources Distribution Simulation: Create a simulation game where students are divided into groups representing different communities with varying levels of resources, access to clean water, and exposure to environmental burdens. The game involves negotiating for resources, facing simulated environmental challenges, and making decisions that impact their community’s health and environment. This activity highlights the complexities of achieving social equity in resource distribution and environmental benefits.

Students participate in a Model United Nations-style debate focusing on global water equity issues. They represent different countries, with a focus on the disparities between water-rich and water-poor nations, including discussions on international aid, technology transfer, and strategies to ensure equitable access to water resources.

Students engage in structured debates on topics such as the impact of industrial development on water resources, the role of government in regulating access to clean water, and the responsibility of businesses towards ensuring environmental equity. This activity encourages critical thinking and understanding of different perspectives.

Students create short documentaries or digital stories that explore water equity issues within their own communities. They can interview local stakeholders, conduct research, and use multimedia elements to tell compelling stories about the challenges and solutions related to equitable water access.

An activity where students must journal every time they use water, to reflect on the importance of water in daily life and understand the challenges faced by those without reliable access to clean water. This experience is followed by a reflection session where students share insights and discuss ways to support water equity.

We provide Canadian educational resources on water practices to promote conservation and sustainability. Our team crafts current and relevant content, while encouraging feedback and engagement.

The Canada WaterPortal is a registered charity, #807121876RR0001

We recognize and respect the sovereignty of the Indigenous Peoples and communities on whose land our work takes place.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved.