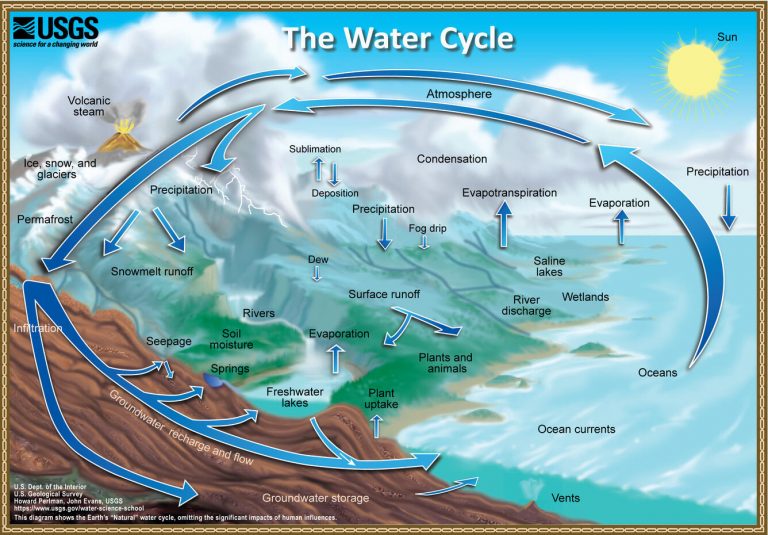

The Hydrologic (or Water) Cycle is a dynamic system. It is a closed system, meaning that nothing can be lost, it can only be relocated to another part of the system.

To start the cycle, water evaporates from the oceans and condenses as clouds that eventually float across the landscape and deliver their moisture in liquid (rain) or solid (snow, ice pellets) form. Some of this water runs off the landscape back to rivers that eventually flow back to the oceans, completing that part of the cycle.

Water that enters the subsurface as recharge similarly flows back to rivers through small to large scale flow systems and discharges through their bases to form “baseflow.” Or it may flow directly back to, and discharge into, the ocean via deep groundwater flow systems.

The diagram shows how the various components of the Hydrologic Cycle manifest themselves temporally and in relation to each other. Although surface water and groundwater in the hydrologic cycle are both part of the same system, the temporal dimensions are very different.

The table below demonstrates the time-variability of water in various parts of the cycle (estimated residence time of various sources of the earth’s water):

| Atmospheric water | 10 days |

| Oceans and seas | 4,000 years |

| Lakes and reservoirs | 10 years |

| Swamps | 1 to 10 years |

| River channels | 2 weeks |

| Soil moisture | 2 weeks to 1 year |

| Groundwater | 2 weeks to 1,000,000+ years |

| Ice caps and glaciers | 10 to several 1,000 years |

Source: Adapted from R. Allen Freeze and John A. Cherry, Groundwater. Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1979

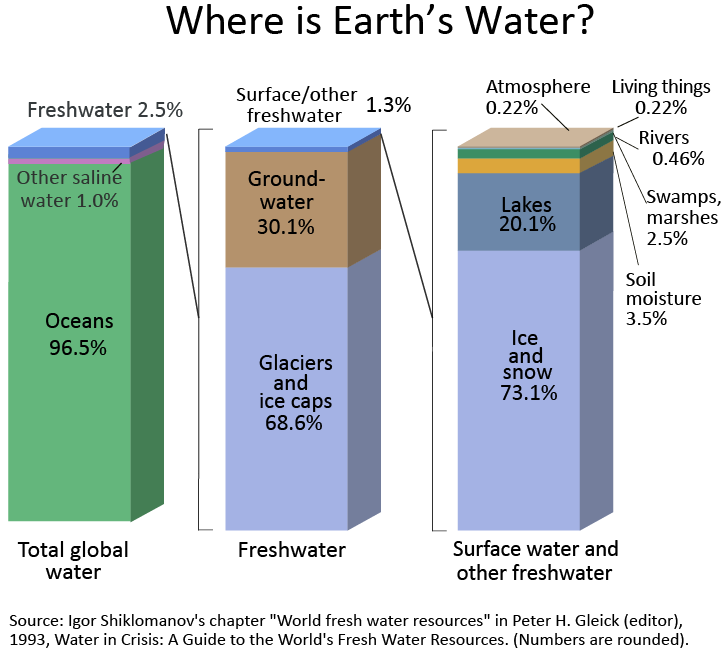

The earth’s water can be categorized into two different types by virtue of it dissolved mineral content (mineralization) or salinity – saline and non-saline sources. The majority of water (96.5%) is saline and is held in the world’s oceans and seas.

The balance, about 2.5%, exists as fresh or non-saline water. Of this fresh water, about 69% is stored in the large ice caps (covering the continents of Greenland and Antarctica), as well as mountain glaciers, while about 30% resides as groundwater. Although 30% of 2.5% may seem small in comparison, it does represent a significant proportion of the world’s fresh water supply.

Compared to groundwater, surface water only amounts to roughly 1.3% of the world’s fresh water supply. Yet interestingly, surface water receives the most attention as a supply source. This is likely due to its ease of access and usual level of freshness with respect to dissolved constituents. Of this 1.3%, only about 0.5% resides in rivers, while the lion’s share (about 23%) is found in lakes and swamps (including wetlands). In contrast, the largest proportion, about 73%, is stored in perennial ice and snow.

From a health and safety perspective, groundwater tends to provide a more reliable quality source of water given the purifying processes that occur as water flows through the sediments and rock formations. In contrast, surface water is more vulnerable to the introduction of pathogens and contaminants originating from activities that occur on the landscape. Consumption of compromised surface water is directly responsible for multitudes of deaths each year in countries with poor water treatment.

We provide Canadian educational resources on water practices to promote conservation and sustainability. Our team crafts current and relevant content, while encouraging feedback and engagement.

The Canada WaterPortal is a registered charity, #807121876RR0001

We recognize and respect the sovereignty of the Indigenous Peoples and communities on whose land our work takes place.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved.