The term “reservoir” [1] can refer to a man-made or natural lake, as well as cisterns and subterranean reservoirs. This article focuses only on man-made reservoirs.

Man-made reservoirs occur when dams are constructed across rivers, or by enclosing an area that is subsequently filled with water. There are two main types of man-made reservoirs: impoundment and off-stream (also called off-river).

Reservoirs can be as small as a pond or as big as a lake. They can differ in size, shape, and location. Due to this vast variability in reservoirs, it can be misleading to make blanket statements about reservoirs without providing more context as to their type and purpose.

Depending on the purpose of a reservoir, operators will fill a completed reservoir with water, let water flow on through the dam and downstream, or leave the reservoir site empty until it is needed.

An impoundment reservoir is formed when a dam is constructed across a river. Impoundment reservoirs are usually larger than off-river reservoirs and are the most common form of large reservoir Saskatchewan’s Lake Diefenbaker is an example of a reservoir created by two dams [2].

Off-stream reservoirs are reservoirs that are not on a river course. They are formed by partially or completely enclosed waterproof banks (e.g. a dry reservoir site reserved for flood mitigation such Alberta’s Springbank Off-stream Reservoir [3]).

The embankments around an off-stream reservoir are usually made from concrete or clay. The size of an off-river reservoir will depend on the topography, how large an area is excavated and how high the embankment is built.

An environmental impact assessment (EIA) must be completed prior to construction on a large or impactful reservoir and dam site. Provincial and Territorial governments have regulatory authority within their jurisdiction and, depending on the details of the project, may require provincial environmental impact assessments. Depending on the size, nature and location of the project, a federal environmental impact assessment may also be required. The federal EIA process [4] is regulated by the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada.

In Alberta, Alberta Environment and Protected Areas is responsible for the laws that are related to EIAs in Alberta (the Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act and the Water Act) [5]. At an inter-governmental level, the 2005 Canada-Alberta Agreement on Environmental Assessment Cooperation is an agreement between the federal government and the Government of Alberta that streamlines the EIA process and ensures that the EIA meets the requirements set out by both orders of government [6].

An EIA may include, but is not necessarily limited to, an analysis of the following:

Depending on the location of the dam and reservoir, stakeholders and rights-holders may need to be consulted before construction can begin.

The construction of a reservoir and dam involves many steps, which are taken carefully to ensure the dam is operational and meets all safety standards and environmental regulations.

Before construction of an on-stream dam can begin, the river must be diverted to make the building process easier. Water can be diverted through constructed channels on the surface alongside the river or through underground tunnels through the rock alongside the river (e.g. Site C in British Columbia [7]). Both methods allow the water to travel downstream of the reservoir site and minimize the amount of water travelling to the construction zone.

A temporary dam called a cofferdam is built above the main site of the permanent dam. The cofferdam is intended to protect the construction site in the event of a flood and may also be used to divert the river during construction.

On wide rivers, a cofferdam may be built on one side of the river to allow water to flow through the other side of the riverbed. The area behind the cofferdam will be drained and the first half of the main dam will be constructed. This side of the main dam will not be constructed to completion. There will still be some holes in this section of the dam. The cofferdam will then be removed, and the water will flow through the holes in the incomplete main dam.

Another set of cofferdams is then built on the other side of the river, and the rest of the main dam is fully constructed. In the final step, the original cofferdam will be reconstructed and the portion of the main dam behind the cofferdam will be completed. Once the cofferdam is removed for the last time, the dam is complete, and water is stored in the reservoir.

In some cases, rather than constructing an on-stream dam, a dam is built off-stream in a topographical depression suitable for holding water (off-stream reservoir). Once the dam is complete, the river is diverted to the off-stream storage site [8].

A crucial step in the lifecycle of building a dam is preparing its foundation. This is the first step in construction for an off-stream dam. For an on-stream structure, the dam foundation is prepared after the river has been diverted.

Once the construction site is drained of water, the dam foundation is excavated. All loose soils and sediment are removed, roots and vegetation are grubbed, and all water is removed from the site until bedrock is exposed.

If a dam is being built using a valley wall on one or both sides, any blocks of the valley wall that are unstable are removed. Hundreds to thousands of cubic metres of unsuitable rock may need to be removed to reach bedrock with the appropriate strength, stiffness, and permeability characteristics required for construction.

The bedrock geology will be surveyed for faults and cavities. Any cavities will be filled with grout to increase the stability of the bedrock and to prevent water from leaking underneath the dam. Concrete may be used to fill larger openings, such as surface cracks, fissures, or irregular surfaces. The foundation surface of the dam will be moistened with water, and then compacted with a roller to increase strength, stiffness, and stability, while reducing permeability.

Finally, if applicable, a mass concrete footing area for an intake tower (a tower used to control water supply for a hydroelectric plant) is constructed and spot rock bolts are installed below the intake tower [9].

Dam construction depends on the type of dam being built. Arch, gravity, and buttress dams are built with concrete and supported by steel. These dams are used for on-stream storage and use the weight of their structure, abutments, anchors, and a solid geological foundation to support them.

Embankment dams (either earthfill or rockfill) are made primarily of soil or rock found in or near the construction area to minimize transportation costs. Erosion is a major concern for embankment dams, and continuous maintenance such as vegetation control is required. The requirements for the foundation are not as extensive for embankment dams as they are for concrete dams.

Once the dam structure is in place, the reservoir is almost ready to be filled. The land that will be underwater is first surveyed for anything that could potentially contaminate the water. Trash and debris are removed. Then, information signs are placed around the reservoir, and roads leading to the construction area are barricaded. The reservoir can then be filled.

For on-stream storage, water will have already begun collecting behind the dam. However, for off-stream storage, water must be diverted to the reservoir.

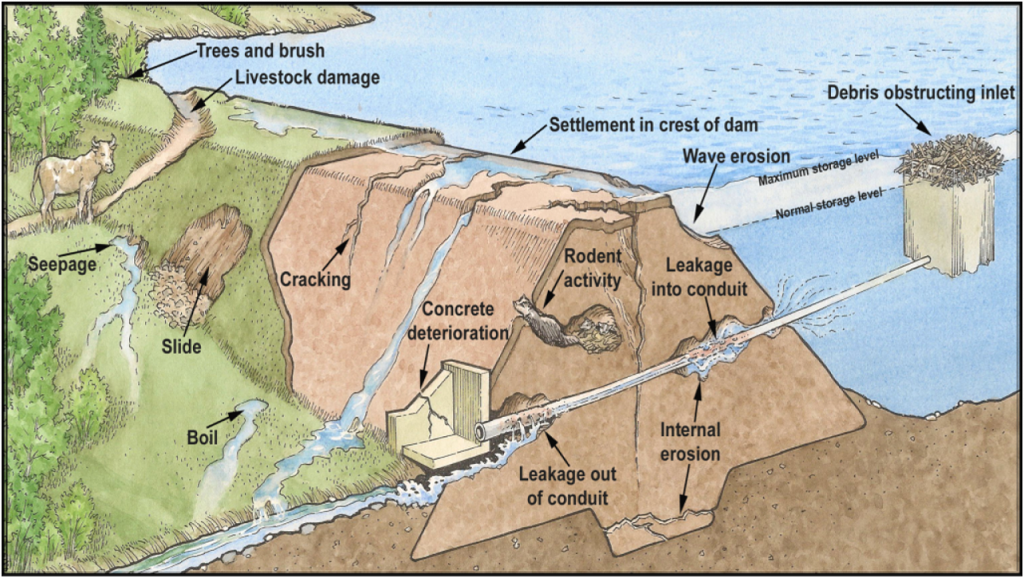

During the filling process, the reservoir site is carefully monitored. Operators watch for seepage of water through the dam and stay alert for mudslides or landslides, which can occur when the soil and new embankment areas around the filling reservoir are inundated and become wetter than normal.

Water quality is monitored at the inflow and outflow of the reservoir and the reservoir water itself. Water quality can be affected by the reservoir, since the water that was formerly flowing is now still. Over time, nutrients in the water can build up and result in the growth of algae blooms; however, when reservoirs are located closer to the mountains, like in Alberta, inflows often have lower nutrient loads, so algae bloom growth is less of a problem. Chemicals can also become concentrated in the reservoir, making the water unsuitable for drinking. To address the risk of this happening, Provinces, Territories and the federal government have various pieces of legislation addressing water quality [10].

Valves are placed in the dam so that water can pass through the dam and go downstream. Valves are tested to ensure that minimum required flows are met and that they can withstand the passage of higher flows if needed. Spillways are common and are often required for safety purposes. A spillway is a part of a dam that allows water to automatically flow over the dam in a controlled manner during a flood event.

In exceptional cases, when a dam needs to pass flows that are larger than what a valve can pass (e.g. during a flood event), a floodgate is used. These floodgates are tested periodically to ensure that safety standards are met.

The dam will “settle” over time. Since a dam is such a large structure, its height will eventually decrease, because its weight will compact it down. The structural integrity of the dam is monitored during this process to ensure that the dam is still functional and safe.

Seepage is also monitored. This is particularly important because as the dam ages, tiny micro-fractures can form and the water can begin to pass through the dam wall. Once water begins to pass through, the hole will get bigger, and the problem will become greater.

The location of the dam is also monitored. The dam may shift slightly upstream or slightly downstream, which would indicate that the structure is unstable. It can also tilt to one side, which is another sign that the dam is unstable [11].

In addition to monitoring the dam structure, water quality is monitored upstream, in the reservoir, and downstream of the dam.

[1] Encyclopedia Britannica, 2023, Reservoir. https://www.britannica.com/technology/reservoir.

[2] Water Security Agency, n.d., Lake Diefenbaker. https://www.wsask.ca/lakes-rivers/dams-reservoirs/major-dams-and-reservoirs/lake-diefenbaker/.

[3] Government of Alberta, n.d., Living by the reservoir: how it works. https://www.alberta.ca/living-by-the-reservoir.aspx#jumplinks-2.

[4] Government of Canada, 2022, Basics of Impact Assessments. https://www.canada.ca/en/impact-assessment-agency/services/policy-guidance/basics-of-impact-assessments.html.

[5] Government of Alberta, 2023, Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act approvals. https://www.alberta.ca/apply-for-environmental-protection-and-enhancement-act-approvals.aspx.

[6] Canada-Alberta Agreement on Environmental Assessment Cooperation, 2005. https://www.canada.ca/en/impact-assessment-agency/corporate/acts-regulations/legislation-regulations/canada-alberta-agreement-environmental-assessment-cooperation-2005.html

[7] BC Hydro, 2020, BC Hydro completes Peace River diversion tunnels. https://www.sitecproject.com/bchydro-completes-peace-river-diversion-tunnels

[8] The British Dam Society, 2023, Building Dams. https://britishdams.org/about-dams/dam-information/building-dams/.

[9] United States Department of Agriculture – Natural Resources Conservation Services, 2012, Part 645 Construction Inspection National Engineering Handbook – Chapter 7: Foundation Preparation, Removal of Water, and Excavation. https://directives.sc.egov.usda.gov/OpenNonWebContent.aspx?content=32418.wba.

[10] Government of Canada, 2017, Water governance and legislation: provincial and territorial. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/water-overview/governance-legislation/provincial-territorial.html.

[11] The British Dam Society, n.d., Dam Safety: Monitor Behaviour. https://britishdams.org/about-dams/dam-information/safety.

We provide Canadian educational resources on water practices to promote conservation and sustainability. Our team crafts current and relevant content, while encouraging feedback and engagement.

The Canada WaterPortal is a registered charity, #807121876RR0001

We recognize and respect the sovereignty of the Indigenous Peoples and communities on whose land our work takes place.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved.