In our province, roughly 308.3 million cubic metres of groundwater is licensed for use to support various activities on the landscape. As indicated in Figure 1, the majority of that licensed amount occurs in the Athabasca Basin (89.3 million m³.) The reason for the large allocation in the Athabasca relates to the oil and gas sector, primarily in situ thermal recovery activities. The next largest allocation is attributed to the Oldman Basin (61.1 million m³), followed by the North Saskatchewan Basin (46.9 million m³.)

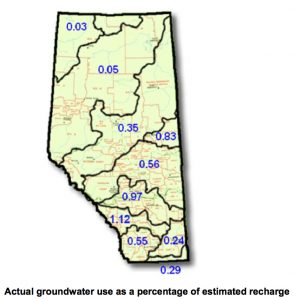

It is evident that all of the major basins in Alberta have groundwater allocations that are not being fully utilized. As such, there is future capacity to develop this resource given the current usage patterns, use as a percentage of estimated recharge, and future use projections.

From a usage standpoint (see chart – upper right), only 29% of the groundwater allocated in the Athabasca Basin is actually used, while only 10% is used in the Oldman Basin. In contrast, a significant percentage of the licensed groundwater the North Saskatchewan Basin is used (47%), but is still quite short of the full allocation.

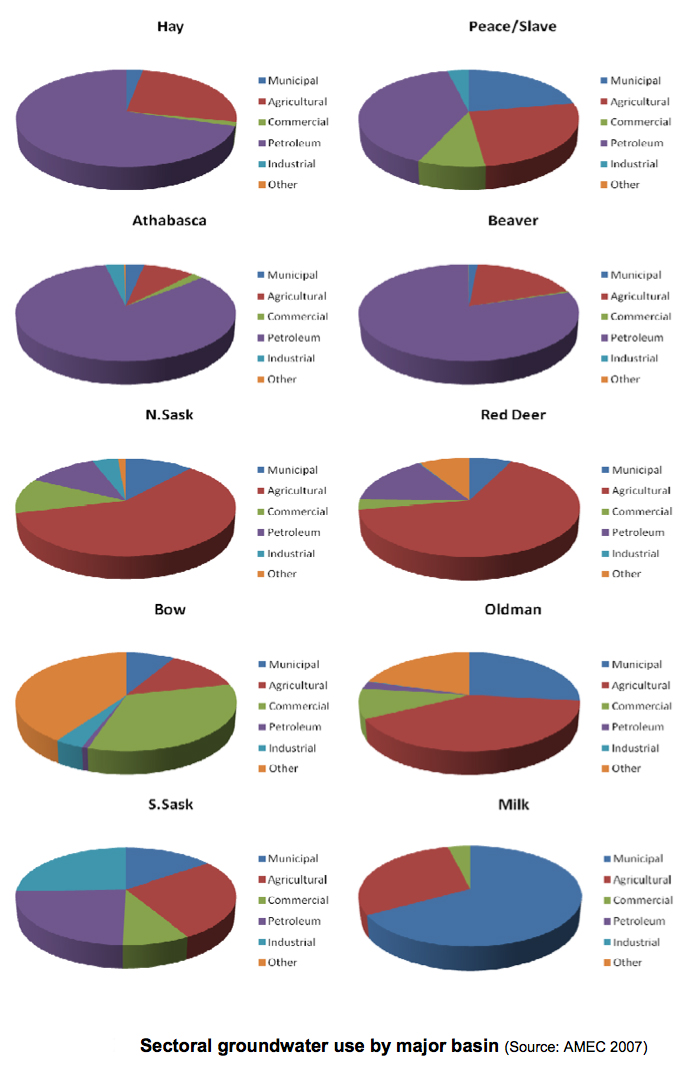

Groundwater that is allocated and licensed for use in Alberta is not equally apportioned between the various major sectors. The chart (left) shows the provincial split between various major users of groundwater.

The clearly dominant user is the Petroleum sector at 43%, with the majority of that water being used to support enhanced oil recovery operations and thermal in situ developments. Next is the Agricultural sector at 30%, where groundwater is used to support irrigation and rearing of livestock. The remaining sectors, in descending order, include: Commercial (9%), Municipal (8%), Other (8%), which includes habitat enhancement and water management initiatives and Industrial (3%).

When the proportional use of groundwater is reviewed by major basin some interesting patterns begin to emerge. The major differences between sectoral users in each basin is shown in the charts (right).

When these differences are reviewed one can see that the largest use of groundwater to support Agricultural (red) development occurs in the North Saskatchewan, Red Deer and Oldman Basins.

Meanwhile, the largest users of groundwater to support Petroluem (purple) development are situated in the Hay, Peace, Athabasca and Beaver River Basins.

With respect to the Municipal (dark blue) sector, the basins with the largest proportional groundwater use compared to other competing activities include the Milk, Oldman and Peace/Slave Basins.

With respect to the Other (orange) use category, which includes habitat enhancement and water management initiaitves, the Bow and Oldman Basins indicate a considerable proportion of groundwater being used to support these activities, at 41% and 20% respectively.

Regardless of where groundwater is being used in our province, it is evident that it serves many purposes to ensure a healthy economy, environment and population.

A considerable amount of water recharges the subsurface annually through percolation and infiltration of precipitation and melting snow. This recharge represents the “renewable” part of our province’s groundwater resource, with water being added at variable amounts each year. Of course, some of this groundwater is removed for use as municipal, agricultural or industrial supply. Understanding the balance between input and output of groundwater is an important concept in the sustainable use of groundwater as a supporting resource for current and future development.

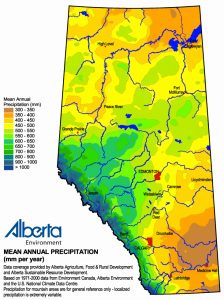

The volumes of groundwater in each aquifer type do not represent a static volume as water is constantly entering and leaving the subsurface through recharge and discharge processes. Recharge of the groundwater systems in our province is directly related to the amount of precipitation received in a given area, the associated terrain, the characteristics of the sediments blanketing the area, land use practices and the evaporative forces.

As is evident in the “Mean Annual Precipitation” chart (above), some portions of our province receive considerably more amounts of precipitation than others.

All things being equal, a region underlain by more granular materials, like sand, will tend to receive more recharge than an area underlain by lower permeability till or clay deposits, as the latter sediments act to impede the entry of water to the water table and underlying aquifers. Given the variability of precipitation received in our province, and changes in sediment types between, and within, the major basins, not all basins (or parts thereof) receive the same amount of recharge.

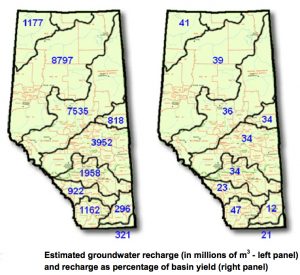

Previous estimates of recharge have been conducted by Alberta Environment to provide some context to our provincial water supplies (AENV 2009). Using the “baseflow separation” approach, the winter baseflow volume province-wide has been estimated to be about 4.8 billion cubic meters. Streamflow during the winter months is often used as an estimate for baseflow since most surface water and the near- surface hydrosphere is otherwise frozen and assumed to be non-contributing. Winter baseflow volume is then extrapolated into a 12-month volume to generate an annual average quantity. This led to the estimate of 14.8 billion cubic meters reported back in 2005.

Further accounting for increases in baseflow during the open-water season (when spring runoff and summer rains add to groundwater recharge and discharge rates) results in an average annual baseflow volume for the province of about 25 billion cubic meters. The second method of estimating recharge used interpretation of surface geology maps, and then estimating the recharge potential of the various soils and underlying geological formations resulting in a total provincial groundwater recharge volume of roughly 27 billion cubic meters per year. The chart (left) shows the distribution of recharge in each major basin of the province and the associated percentage of basin yield.

Put into perspective, anywhere from 25% to 45% of the surface water volumes generated annually in the province is provided by baseflow contribution, or discharge of groundwater to the rivers and streams. In some cases these contribution can be much higher (e.g., 68% of annual runoff for Jumping Pound Creek in the Bow Basin – AMEC 2009), underscoring the importance of groundwater to river flows and the preservation of aquatic habitat.

It should be noted that the techniques of “baseflow” estimation of recharge, as opposed to the “baseflow separation” techniques, are varied in their approach. Nonetheless, the estimates provided indicate a range of between 15 and 30 billion cubic meters of recharge to the province per year, with the bulk occurring to the proportionally larger and wetter basins.

To provide additional context, a comparison of the actual amount of groundwater used in each major basin with the estimated amount of recharge has been made. The chart (right) shows the amount of groundwater used in each major basin as a percentage of the estimated average annual recharge received in that basin. It is evident that generally less than 1% of the estimated recharge that enters the basins each year is accessed and used, with the largest percentage occurring in the Bow River Basin at 1.12%, and the Red Deer River Basin at 0.97%.

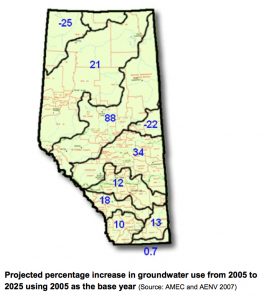

Future trends for groundwater use have been projected for the various major basins throughout the province (AENV and AMEC 2007). Projections have been made for various scenarios including low, medium and high use. The chart (right) shows the projected percentage increase in non-saline groundwater use for the medium use scenario (to the year 2025, using 2005 as the base for comparison).

It is apparent that a considerable increase in groundwater use is projected to occur in the Athabasca Basin (88%), followed by the North Saskatchewan (34%). The substantial increase in projected groundwater use in the Athabasca Basin is in relation to continued in situ thermal developments.

In contrast, declines in groundwater use are projected for the Beaver and Hay River Basins possibly due to anticipated declines in oil and gas activities, or increasing use of saline water as an offset to non-saline sources.

We provide Canadian educational resources on water practices to promote conservation and sustainability. Our team crafts current and relevant content, while encouraging feedback and engagement.

The Canada WaterPortal is a registered charity, #807121876RR0001

We recognize and respect the sovereignty of the Indigenous Peoples and communities on whose land our work takes place.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved.