As indicated previously, the groundwater systems underlying our province are not static, and respond to the balance between supply (recharge) and demand (use). Human-induced influences such as groundwater withdrawal will have the obvious effect of lowering water levels in an aquifer, or aquifers depending on the degree of connectivity. These effects might manifest themselves locally, but can extend over larger areas under scenarios of intensive use or dewatering to support construction or mining activities.

Additionally, changes to the landscape occurring from alteration of the land cover can also have a significant influence on aquifer water levels by changing the ability of precipitation and melt-water to recharge the subsurface. For example, the differences in soil moisture conditions and potential for groundwater recharge can be significant between more shaded, forest covered areas as opposed to grassland areas or cultivated land.

The image (below) shows a LANDSAT image taken from an area within the Beaver River Basin showing the differences in land cover (top panel) and the resulting soil moisture conditions (lower panel).

Outside of these human effects, there are large-scale climatic effects that can have a significant influence on the hydrology of Alberta Basins. In particular, there are two influencing climate phenomena that can have an influence on provincial water supplies. The first of these phenomena is the El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, which has a return period of two to seven years and can last anywhere from six to eighteen months during its various phases. The warm El Niño phase tends to bring increased temperatures and reduced precipitation conditions during the various seasons. The opposite of the El Niño phase is the La Niña phase, which tends to bring generally cooler and wetter conditions to Alberta.

Typical climatic responses to El Niño and La Niña events indicate the general departure of temperature and precipitation from seasonal normals.

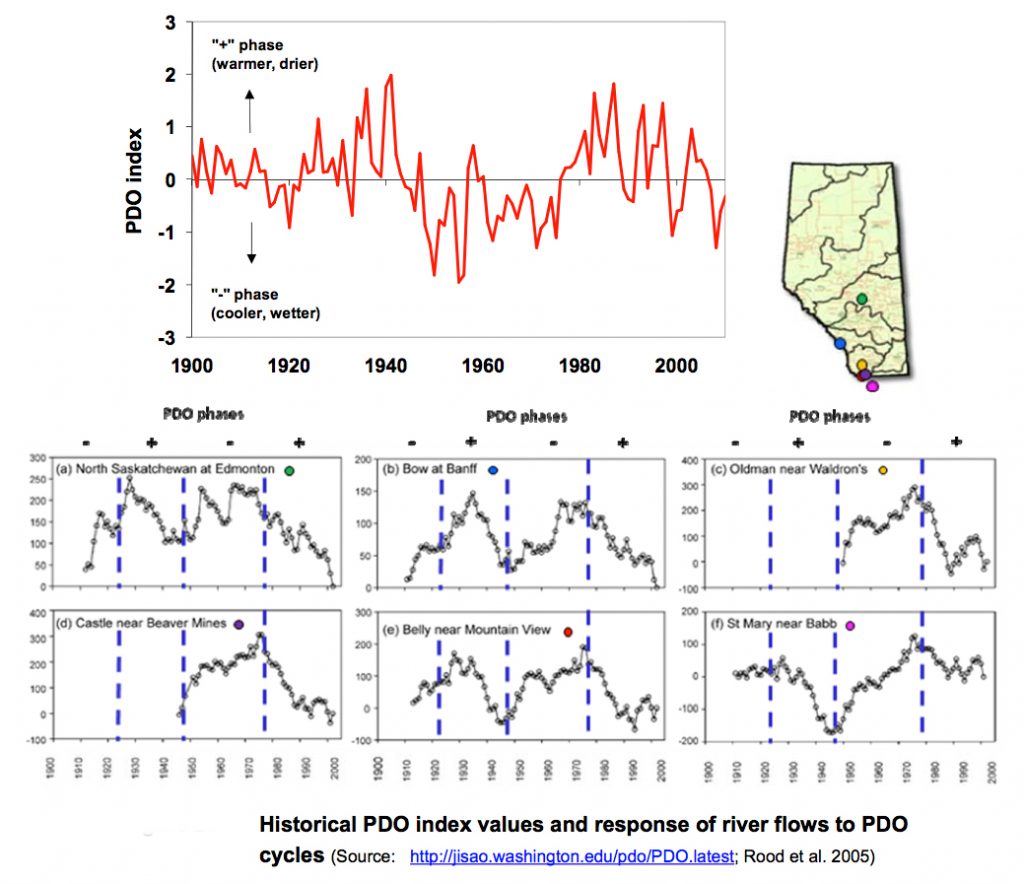

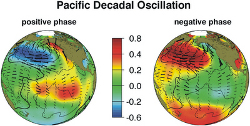

Another longer timescale phenomenon that influences climatic conditions in Alberta is the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) is a climate phenomenon believed to be caused by a large scale sea-surface temperature pattern of the North Pacific Ocean that affects the jet stream over North America. This climatic event operates on a return cycle of 25 to 30 years between positive (warmer and drier) and negative (cooler and wetter) phases. Learn more, about the various PDO, El Niño and La Niña events that have occurred since 1950.

Research and knowledge of the PDO phenomenon is a developing area (Kiffney, Bull and Feller 2002) and the full effects on Alberta’s water resources is currently under research. Needless to say, seasonal variability in average temperatures and amounts of precipitation received to the various basins in Alberta will have a notable effect on recharge conditions, and hence groundwater levels within Alberta’s unconfined and confined aquifers.

A review of the effects that the PDO has on river flow characteristics was completed by Rood et al. (2005) for various river gauging stations in Alberta and northernmost Montana. The results provided in this assessment showed some degree of correlation between this climate phenomenon and the deviation of flow conditions from the mean flow of each river. Click on the image (above) to learn more, about how this deviation from mean flow has manifested itself over the various phases of the PDO for each river, with higher mean flows tending to occur during cooler (wetter) phases of the PDO and lower mean flows occurring during warmer (drier) phases.

There is also some evidence to suggest that the PDO may have some influence on snowpack conditions in certain headwater areas of the eastern slopes.

To date, an assessment of the effects of the ENSO and PDO cycles on groundwater resources beneath Alberta has not been completed. Nevertheless, Alberta Environment operates a groundwater observation well network within the province that has been operating at least since the mid-1980s and in some cases the period of record for certain wells has been shown to extend further back to the mid-1970s.

A review of available hydrographs for selected wells located within the various major basins of Alberta was completed as part of this study to assess temporal trends and the possible influence of climatic events like the ENSO and PDO phases. Unfortunately, the periods of record for the majority of wells does not extend far enough back in time to resolve such influences with any degree of confidence. However, some apparent trends are noticeable following a review of the records on file. View a summary of general water level trends (by major river basin) extending over the period of 1989 to 2009.

Although general trends in the historical groundwater level records appear across the province, the connection to climatic events such as the ENSO and PDO cycles still is unclear, and suffers from a lack of sufficient information. Nevertheless, the preceding review does demonstrate the dynamic nature of groundwater in response to changing conditions, and the need for continued monitoring to assess connections with climate cycles and changing conditions, and the associated vulnerability in response to supply and demand patterns and land use practices.

We provide Canadian educational resources on water practices to promote conservation and sustainability. Our team crafts current and relevant content, while encouraging feedback and engagement.

The Canada WaterPortal is a registered charity, #807121876RR0001

We recognize and respect the sovereignty of the Indigenous Peoples and communities on whose land our work takes place.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved.