According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the term “balance” refers to:

When operating under the principle of sustainability, consideration is given to the interactions of competing system components and the management of those components to maintain a suitable balance so as not to adversely affect the system. With respect to water, this relates to a balancing between supply and demand and an acknowledgement and understanding of the external forces that can affect the supply side of the equation (e.g., climate variability or change).

The most current water balance for the province of Alberta was generated in 2005 by the Government of Alberta. The diagram shows the results of this water balance, indicating the major inflows (precipitation, runoff and surface water flows entering the province) and outflows (evaporation and transpiration, flow leaving the province).

Of the water that is received in our province, the recharge to the subsurface was estimated at the time as 14.8 billion cubic metres (m3). For context, this amounts to the volume of about 5.9 million standard Olympic-sized swimming pools each year (50m long x 25 m wide x 2 m deep). Additionally, all 14.8 billion m3 of recharge was interpreted to discharge to the various rivers and streams as baseflow contribution.

Updates to this estimate of groundwater recharge have been made since the 2005 figure. The new paradigm presented in this study, is that some of the recharge to the subsurface environment actually becomes part of a stored volume of water that exists in various locations within the overall groundwater system of the province. It is this recharge that is responsible for the increase in water levels measured in water wells and observations wells across Alberta.

In contrast, the drainage of this recharged water to surface water feature, such as lakes, wetlands, streams and rivers, in combination with the variable influx of precipitation due to changing climatic conditions is responsible for declining water levels noted in some of these same wells.

As a result, the balance of recharge and discharge is reflected in the amount of stored groundwater held beneath the province at any given time.

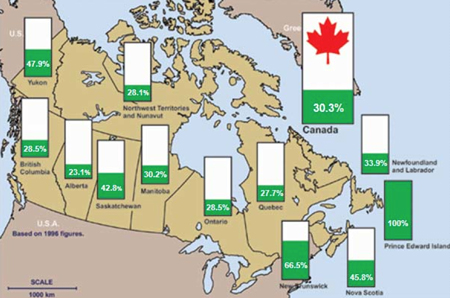

Groundwater is an important resource to many residents of Canada. In Prince Edward Island, groundwater provides 100% of the water supply to its residents. According to Statistics Canada, about 30% of the Canadian population (or roughly 10.4 million people) rely on groundwater as a source of water supply.

In Alberta, the percentage of the population reliant on groundwater as a supply source is about 23%. Based on 2010 population estimates, this equates to roughly 840,000 residents.

Although this percentage may seem small, the reliance on groundwater in certain locations like areas where there is restrictions on new licences for surface water or groundwater under the direct influence of surface water (South Saskatchewan River Basin), is increasing. As a result, the importance of groundwater in sustaining local populations and businesses is becoming apparent.

In water-short areas of the province (southern Alberta) water supplies are currently managed through a series of storage reservoirs and management structures. The storage shortfall of 2001 and the need to re-allocate licensed volumes of water provides an example of how precarious the situation can become in the face of extended drought or water deficit conditions.

As such, groundwater exists as a potentially important source of water supplies in time of need, and can be used to offset diminished supplies of surface water. The concept of “drought-proofing” communities in advance of potential future mega-droughts (as indicated by palaeoclimate reconstructions using proxies such as tree-rings and lake sediments) is gaining popularity among water managers responsible for serving water-short areas of the province.

Read more about the role and use of groundwater (Environment Canada)

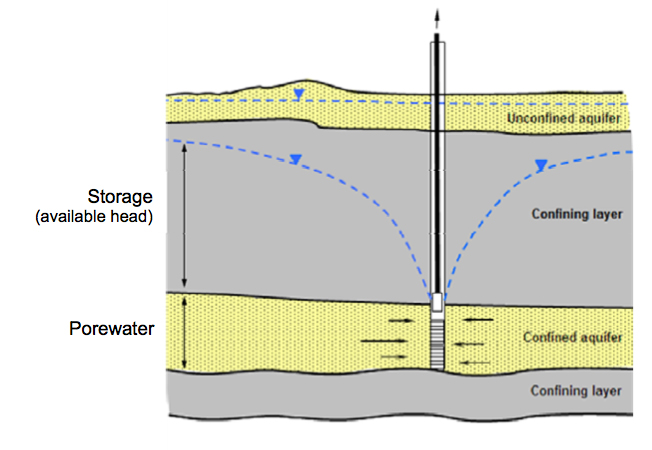

Volumes of non-saline groundwater exist in two forms:

The total volume of pore water for a given formation is determined by determining the saturated thickness of an aquifer and multiplying by its average total porosity:

VT = A * d * η Equation (1)

In the above equation VT = Total Pore Volume (m3), A = Area, or areal extent of the aquifer (m2), d = Average Saturated Thickness, for a confined aquifer this is equal to the thickness of the aquifer (m), and η = Average Total Porosity, which is equal to the ratio of void space within a total volume of material.

Total storage volume, on the other hand, is calculated by assessing the volume of water that is released from storage as a confined aquifer is pumped. This volume occurs as a result of the expansion of water and compression of the aquifer as the hydrostatic pressure is reduced.

The amount of water available to be released from storage is defined as follows:

Vs =A*d*Ss*H Equation(2)

In the above equation Vs = Total Storage Volume (m3), A = Area, or areal extent of the aquifer (m2), d = Average Saturated Thickness – for a confined aquifer this is equal to the thickness of the aquifer (m), Ss = Specific Storage (m-1) and H = Available Hydraulic Head, which is equal to the average height of the water surface (or potentiometric surface) above the top of the aquifer (m).

These two volumes of water comprise the total resource of groundwater residing within a given basin or area. However, it is uncommon for water levels in a confined aquifer to be drawn down below the top of the aquifer. In cases such as this, significant aquifer damage can occur as a result of matrix collapse. Overuse of an aquifer can lead to such occurrences. That is why it is important to understand a groundwater system before it is exploited to any large extent.

Estimates of the volume of non-saline groundwater residing in the various aquifer types, (summarized below) were derived using the above equations and methodology.

| Aquifer type (km3) | Median pore volume (km3) | Median storage volume (km3) | Median useable volume (km3) |

| Alluvial | 34.3 (16.2 to 55.4) | 1.37 (0.6 to 2.2) | 22.7 (5.3 to 18.3) |

| Buried Channel | 135.3 (6.4 to 1,526) | 0.08 (less than 0.01 to 4.1) | 0.04 (less than 0.01 to 2.07) |

| Bedrock | 1,122 (166 to 5,620) | 12.5 (5.5 to 209) | 6.3 (1.1 to 18.1) |

Note: the range of values shown in brackets represents the 5th and 95th percentiles, respectively (1 km3 = 1 billion m3)

These estimates represent the first attempt at providing an overall assessment of provincial groundwater supplies. As such, the volumes generated represent a first order approximation and will no doubt be refined as more information on the subsurface is generated in the coming years, and interest in groundwater as a viable supply source grows. Total volumes, and useable volumes based on prevailing sustainable yield guidelines and policies, have been included.

In Alberta, non-saline water is defined under the current Water Act as any water that possesses a mineralization (as total dissolved solids content, or TDS, in mg/L) equal to or less than 4,000 mg/L. This water can reside in unconsolidated or consolidated bedrock formations situated anywhere from surface to depths exceeding several hundreds of meters.

The interface that demarks the change from 4,000 mg/L TDS to greater values is commonly referred to as the Base of Groundwater Protection (BGP). Considerable work has been done by the province of Alberta (Alberta Geological Survey) to define where and at what depth this interface exists. This is the depth that any industry can have an effect on non-saline groundwater which is why mitigation is required to ensure such events don’t occur. The mitigation, commonly employed by industry, is to provide a steel casing and cement seal from the surface to the BGP.

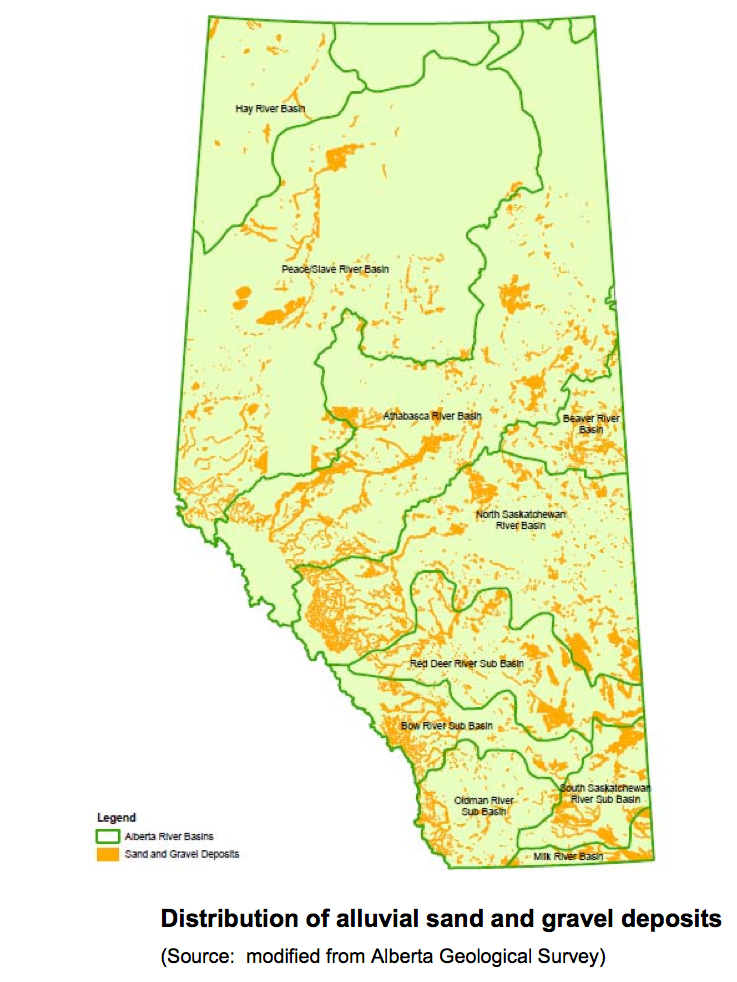

Alluvial aquifers in the province of Alberta comprise the unconsolidated sand and gravel deposits that we commonly see along existing river beds, the occasional road cut or sometimes in an excavated gravel pit. These granular deposits tend to possess very high permeability due to the presence of significant void space between the sand, gravel and silt grains. As such, these deposits can yield significant quantities of water and because these deposits are close to surface, the water quality tends to be quite fresh.

The majority of these deposits represent recent (within the last few thousand years) sediments deposited by water flowing across the landscape along relatively well-defined drainage ways. In some cases, these deposits have been buried under layers of sediment that were deposited by glaciers that advanced and retreated across the Alberta landscape during the most recent continental glaciations, which ended some 10,000 to 15,000 years ago.

The diagram (right) shows the distribution of major sand and gravel deposits across the province of Alberta. It is evident that some areas of the province benefit from substantial accumulations of these materials, and in turn the potential to develop groundwater resources if needed. Because these deposits reside close to the surface, costs of developing groundwater from these intervals is greatly reduced.

Some concern is mounting with respect to the mining of these alluvial sand and gravel deposits for aggregate materials to support construction activities. Mining of the aggregate material from its natural resting place requires dewatering of the sediments, which can lead to adverse effects to nearby users or sensitive ecological receptors and groundwater dependant ecosystems. Removal of this material also diminishes the water storage capacity and can disrupt subsurface flow systems. Consideration of these effects is therefore needed when developing groundwater resources from alluvial aquifers.

From a groundwater quality perspective, alluvial aquifers are the most sensitive type of aquifer to influences on the landscape. Depending on the type, extent and thickness of sediments covering these aquifers, the application or spills of chemicals and leaking of septic systems can significantly affect the quality of groundwater over localized areas, sometimes referred to as point-sources, or very broad areas (non-point sources).

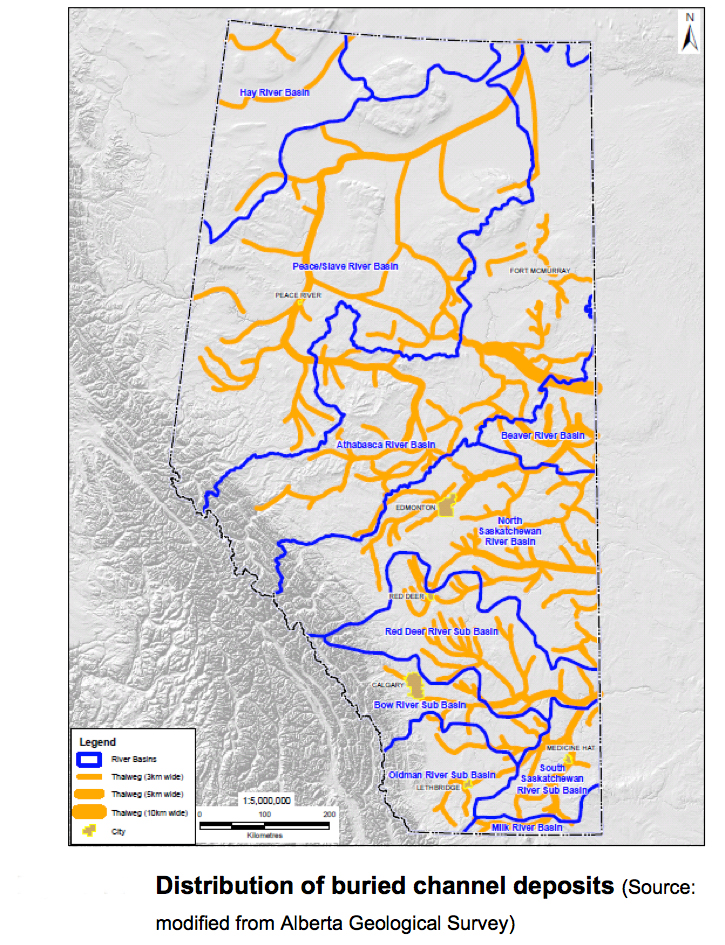

Lying beneath the surface of our province is an intricate network of buried channels formed prior to the last continental glaciations of North America (the ancestral drainage network) or formed during the process of erosion by glacial melt-water formed during warmer periods.

During the last continental glaciation, up to four episodes of ice advance and retreat occurred in response to the varying climatic conditions. During each of these events, deposits of sand and gravel were laid down in various locations across the province as broad outwash plains, fluvial channels and lacustrine (lake) deposits. These porous and permeable intervals were then subsequently buried under less permeable deposits of till, thus forming confined aquifers. The depositional features of interest here are the buried channels, which host considerable quantities of water in the pore spaces of the sand and gravel deposits.

The known network of buried channels beneath our province is shown in the diagram (right). As indicated, the network is extensive across the Alberta plains area east of the foothills area (or deformed belt) of the Rocky Mountains.

The morphology and overall sediment compositions within each buried channel varies. Within each of these features resides quantities of groundwater that can be used to supply rural populations and associated economic activities including rearing of livestock, cropping, mining and oil and gas recovery. Some of these buried channels are currently accessed as supply sources to support such activities.

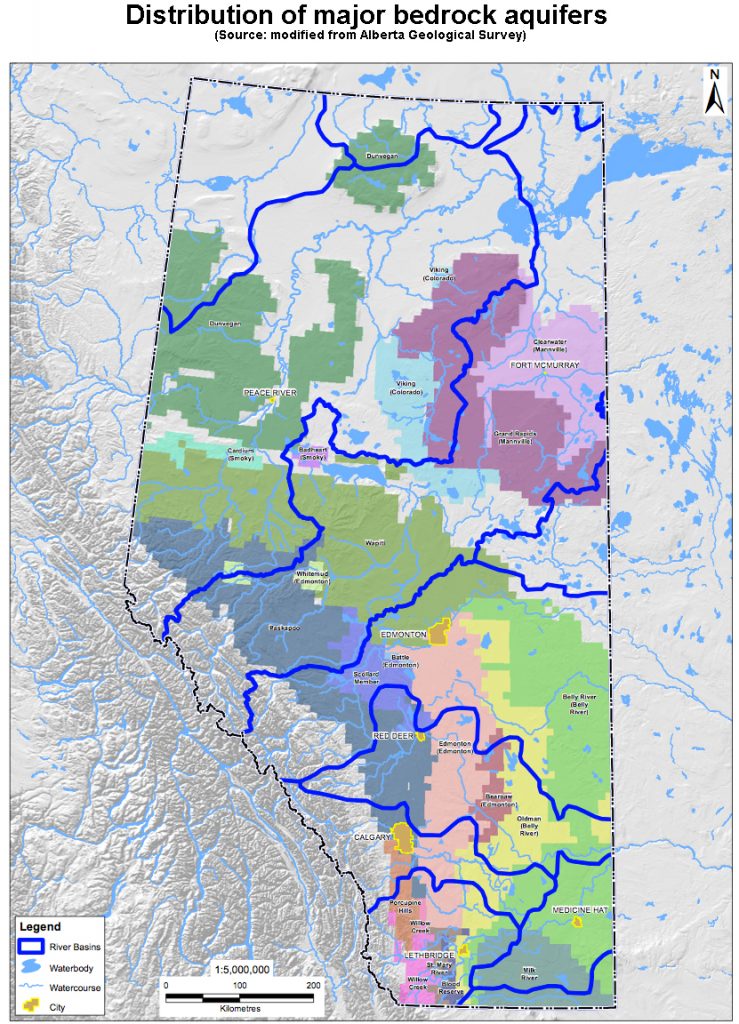

In addition to the vast accumulations of granular sediments comprising alluvial aquifers and buried channel deposits, a number of bedrock formations possess water-bearing properties and contain significant quantities of useable groundwater (Figure 13). These bedrock formations tend to be comprised of thick alternating sequences of sandstone, siltstone and shale deposited in the foreland basin of the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin over the last 100 million years (i.e., Cretaceous to Tertiary Periods).

There are a number of bedrock aquifers that are currently being utilized in Alberta. Learn more about each formation according to approximate age, origin and dominant lithology (physical characteristics).

The most significantly used bedrock formation containing useable quantities of non-saline groundwater is the Paskapoo Formation of more recent age. An estimated 200,000 wells have been drilled into this southern Alberta formation, with about 70,000 considered active (GoA 2010). By international standards, the Paskapoo Formation would not be considered a “classic aquifer system” as the yield capability is restricted by its dominant fine-grained lithology and highly variable spatial-character with respect to sandier and more permeable intervals.

A modern day analogue of the type of depositional environment responsible for such a formation exists in the Columbia Valley of the East Kootenays. There, the Columbia River winds its way from the headwaters of Columbia Lake northward towards Golden through a series of wetlands, depositing granular materials within distinct channels in stacked sequence or as over-bank deposits of limited extent. As such, the low energy depositional environment is prone to the accumulation of fine-grained sediments (silt and clay) which interrupt otherwise continuous and connected sandy intervals.

The other bedrock aquifers of Cretaceous age do supply, or have the potential to supply, large quantities of usable groundwater but are more prone to highly mineralized porewater due to interaction with higher salinity formations deposited in the Cretaceous sea that extended across Alberta at the time. Nevertheless, in areas where these bedrock formations come close to the surface, many residents and businesses in Alberta access the water supplies contained within for personal or economic use.

We provide Canadian educational resources on water practices to promote conservation and sustainability. Our team crafts current and relevant content, while encouraging feedback and engagement.

The Canada WaterPortal is a registered charity, #807121876RR0001

We recognize and respect the sovereignty of the Indigenous Peoples and communities on whose land our work takes place.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved.