This is a summary of the presentation delivered by Kim Sturgess at The Schulich School of Engineering at the University of Calgary on June 4th, 2018.

In early 2018 the world’s interest and anxiety was captured by the announcement of Day Zero and the online clock counting down toward the projected time when the household taps of Cape Town would have to be turned off and water would be delivered by truck to city residents. Media around the world began talking about water scarcity and examining factors threatening the water supply of other cities. There was a general increase in awareness that municipal water supply could run out and what that could mean for a city. This global ‘conversation’ about water scarcity was a good thing, but there have also been negative consequences to the sensational announcement of #dayzero.

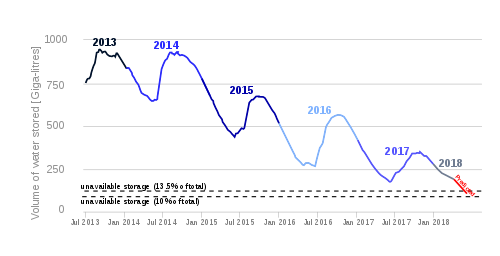

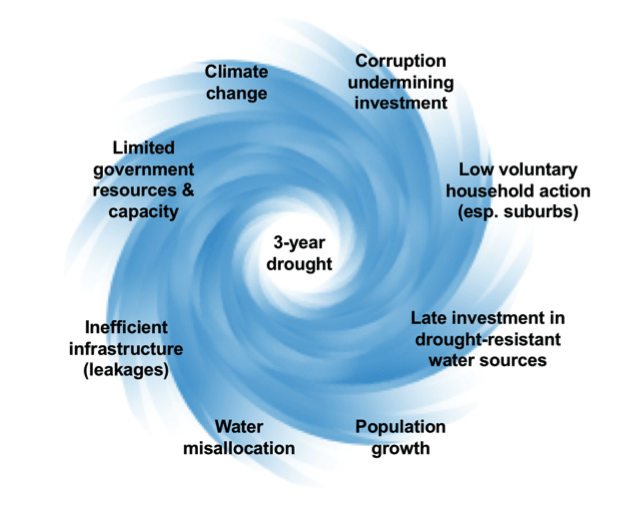

Cape Town, South Africa is an example of numerous social, environmental, and political factors combining to create a water crisis for such a large city. There is significant inequality in access to water in Cape Town, the township areas of the city rely on communal taps and residents use very little water while in the wealthy neighborhoods private homes have large, lush gardens and swimming pools. Environmental factors include that Cape Town is already in a dry region and had been experiencing a multi-year drought leading up to the water crisis in 2018.

Political issues exacerbated the crisis. National, provincial, and municipal government bodies disputed responsibility for the growing water crisis for several years. Corruption and partisan politics also played a role in the lack of resources allocated to the region of Cape Town’s water management infrastructure even when the city was clearly approaching a crisis. The political response to the water crisis was to declare a national disaster and conduct a massive water-saving and educational campaign among residents to avoid the so-called Day Zero.

Action on the ground in response to the water shortage included implementing water restrictions of 50 liters per person per day and steep, graduated tariffs for consumption beyond this amount. Restrictions were placed on agricultural, commercial, and industrial water use. Additionally, efforts were made to reduce system leaks and losses, an emergency water desalination plant was contracted for a 2 year period, farmers released water from their private reservoirs, and many private users paid to access groundwater through borehole wells. A very significant part of the water saving action was individual citizens reducing their household water consumption through numerous behavioral changes including bathing less and re-using wash-water for flushing toilets.

This suite of on the ground actions was successful and water demand across the city of Cape Town was reduced significantly. Rainfall began early in the rainy season and the reservoir system began to refill, relieving the extreme crisis situation.

Was announcing #dayzero a good thing?

There are both positive and negative consequences resulting from the announcement of Day Zero. The extreme water crisis of turning off household taps for a city of approximately 4.4 million people was avoided, and the mobilization of private citizens behavior demonstrated the scale and speed of change in water demand that is possible. The crisis also caused wealthy residents of Cape Town to better understand the restricted water access that poor residents in the townships have always been living with.

On the other hand, because the water crisis got so bad before action was taken, there were significant economic impacts across the region. Tourism, agriculture, wine exports, and water reliant businesses like car-washes all have been hit hard by #dayzero. The unregulated and unquantified drilling of borehole wells and draw on groundwater is also a significant concern. The local aquifer may be drawn unsustainably, potentially resulting in an even bigger water crisis in the future. Private companies and wealthy citizens are investing in desalination plants and independent water systems meaning they do not pay municipal water service fees, resulting in less money for the city to develop better water infrastructure to fix leaks and inefficiencies, leading to potential future water scarcity.

For the global community, #dayzero focused attention on the possibility of water scarcity for cities around the world and what that could mean. The environmental, social, and political causes of the water crisis in Cape Town are not unique to South Africa, and hopefully citizens in other at-risk cities recognize this and take preventative action.

The lessons for Alberta are:

- Act NOW – Drought management tools, policies and actions must be deliberated and designed before crises hit

- Engage those that know the watershed best – Involve informed water stakeholders in the design of drought management and mitigation programs

- Educate and build awareness – Educate citizens about their water risks, responsibilities and options

- Don’t cry WOLF – Politics should not govern water management decisions, and especially not through a crisis for risks of making the situation worse down the road

Click on the link to download a PDF copy of the presentation Cape Town Water Crisis Presentation – Kim Sturgess