Reservoir operators monitor the water level of the reservoir as well as flow downstream. A certain quantity of water needs to be released from a reservoir to maintain good water quality and a healthy aquatic habitat. Many aquatic species, including plants and animals, are sensitive to changes in their environment and require a minimum amount of water to survive.

Factors that inform operators on how much water to release downstream include: meeting aquatic ecosystem needs; amount of water lost to evaporation; amount of water trapped in the spongey riparian zone; and water license holders that divert water from the river. All of these factors need to be considered when an operator determines how much water to send downstream.

Typically, in the winter months the streamflow downstream of a reservoir are much greater than they would be in a natural system without the reservoir due to winter releases (e.g. hydropower generation). This ensures a steady, stable supply of water in the river through the winter months for waste assimilation. In the spring, a reservoir will generally be at or near to its minimum storage capacity. During this period, the dam and associated infrastructure are often inspected and the reservoir area will be examined. Reservoir refill usually begins in mid-June and will fill at variable rates depending on weather patterns and snowpack conditions, typically targeting beginning of August for full reservoir refill. The remaining flows are then sent downstream. The reservoir is then ready to supply water to downstream users for another winter.

Given that a dam is a block in a river, it will accumulate all sorts of things behind it (primarily sediment). However, debris, trees, rocks and other objects can also be collected behind a dam during high flow events such as floods.

In order to know what to remove from a reservoir, bathymetric surveys can be completed to map the bottom of the reservoir. These surveys might reveal that there is a large buildup of sediment in one specific area or throughout the bottom of the reservoir. If the reservoir is found to have a large accumulation of sediment, operators may investigate dredging as an option to remove the sediment.

A cost-benefit analysis is completed before dredging begins to make sure that the benefits outweigh the costs.

Another method used to remove sediment is to open up reservoir gates at the bottom of the dam. Operators can periodically open these gates to release sediment downstream.

Whether dredging or gates are used to remove sediment is dependent on how quickly materials gather behind the dam. In some places there is a high chance of sedimentation, while in others it is not a problem. The type of sediment that accumulates also plays a role. In Alberta, a large portion of sediment is sand and gravel. If silt and mud were collecting instead, reservoirs would need to be dredged frequently. No large reservoirs in Alberta have been dredged.

When you look at a river, you can see water flowing downstream. However, there is more than just water flowing in a river. Sometimes large items, such as logs, float down the river. There are also pieces of rocks, sand and soils called sediment that move downstream with the river. Usually sediment that is carried down a river is very small or fine-grained. Sediment can range in size from sand, to silt to mud to gravel.

During high-stream events such as floods, sediment can be larger and coarser-grained than normal. Sediment can get as big as gravel-sized particles (e.g. pebbles) and sometimes even boulders!

Worldwide, as much as 13 billion tonnes of sediment travels from rivers to seas every year, while two to five billion tonnes of sediment are trapped in reservoirs [1].

The sediment that flows in a river can come from the landscape of the watershed or the river itself. Sediment is created during the processes of weathering and erosion. Weathering is a natural process that breaks rock down into smaller and smaller particles. There are two types of weathering: physical and chemical.

Physical weathering includes breaking rocks down through water, ice, wind and temperature change. In Alberta, a type of physical weathering called “freeze-thaw” weathering is common. Water collects in cracks in rocks. When the temperature goes down in the winter, the water freezes and expands, making the crack even larger. In the spring when the ice thaws the water flows out of the crack and takes sediment with it.

Chemical weathering refers to alterations in the rock on a chemical level. For example, acidic rainwater falling on rock can cause the rock to dissolve. Rusting is also a form of chemical weathering where the oxygen in the air weakens the rock. Plants can also cause physical and chemical weathering. A shrub with deep roots might crack through rock, causing physical weathering. The same shrub might produce acidic compounds which dissolve the rock.

Erosion is different than weathering. While weathering is the process of a rock breaking down where the rock sits, erosion is the process where sediment is broken off a rock and is carried to another location. Wind or flowing water are the two main drivers of erosion. In some cases, wind can blow sediment off a weak rock (such as sandstone) and can carry this sediment to a nearby river. Other times, sediment that is broken off a rock by falling rain can be carried to a river through runoff. Within a river, it is the river itself that causes the most erosion. As the water courses through the valley, it breaks off sediment from the river bed and transports it downstream.

Weathering and erosion is more prevalent at higher elevations or upstream in a river. The Rocky Mountains face heavy weathering and erosion. The sediment that is eroded in the headwaters is transported downstream. Deposition is the opposite of erosion. The eroded sediment is transported by the river and deposited downstream. A portion of this sediment will eventually reach an ocean or a lake but some is deposited along calm reaches in the river, lakes or along a riverbank.

Sediment will flow with quick moving water until a river reaches an ocean or lake. If a river flows into a reservoir, the sediment will fall to the bottom of the reservoir because the water in a reservoir is so still. Over time, as more and more sediment is captured by the reservoir, the amount of water that can be held in the reservoir is greatly reduced. The analogy is a bucket filled with sand cannot hold as much water as a bucket that is empty.

Some dams are constructed with a gate that is designed to release sediment from a river downstream into the river. Sometimes a reservoir can be dredged (a process where sediment is removed from the reservoir) to increase its storage capacity. This is typically done in reservoirs that collect a lot of smaller particles like silt and mud, unlike the rivers in Alberta that have more gravel and sand.

Glenmore Reservoir is located on-stream on the Elbow River in western Calgary. The reservoir was constructed in 1932. In 1968 the reservoir was surveyed to assess the amount of sediment that had accumulated over the years. In the 36 years that the reservoir had been operating, it had lost ten percent of its storage capacity due to sedimentation.

Currently, the bottom of the reservoir is covered in silt, sand and clay. The amount of silt entering the reservoir is relatively consistent annually. During years with floods, the amount of sediment flowing through the reservoir is much higher, however a large portion of this sediment flows over the spillway, downstream of the reservoir [2].

There has been an ongoing debate regarding dredging Glenmore reservoir. There is potential to increase the total water storage capacity and increase the amount of live storage (which is used for flood control). However, the benefits might not justify the costs. The City of Calgary’s Expert Management Panel on River Flood Mitigation concluded in 2014 that the benefits of dredging Glenmore would only be temporary, the increase in storage capacity would be small, and there could be additional consequences such as lower water quality due to disturbing the sediments. The report also stated that the cost of dredging would end up being millions of dollars [3].

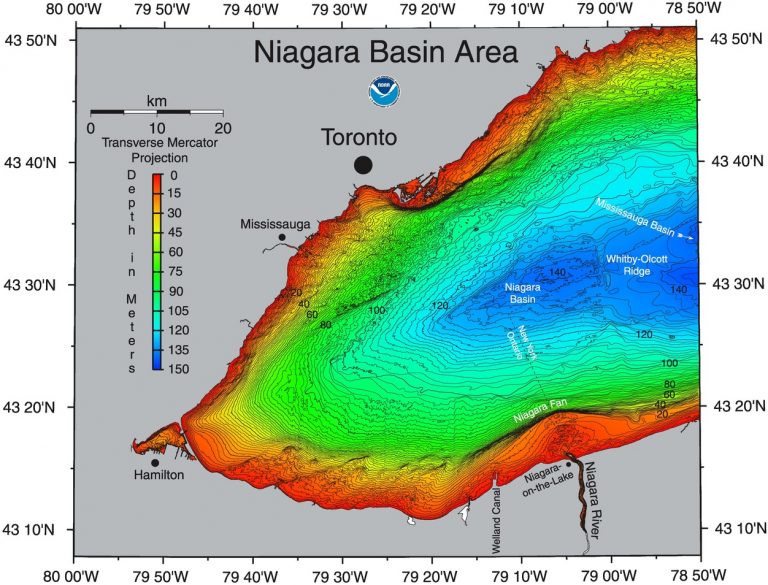

Bathymetry is the mapping of an underwater surface, such as the seafloor or the bottom of a lake or reservoir.

In order to map a reservoir, the topography of the area is recorded before a reservoir is filled. Once the reservoir is filled, bathymetric surveys are used to monitor the bottom. These surveys are useful, because overtime sediment will build up in the reservoir and the surveys can help determine the amount of sediment.

Dredging is the act of scraping out accumulated debris and sometimes sediment that has accumulated at the bottom of a reservoir. Dredging is often very expensive so before it is undertaken a full cost-benefit analysis is completed to ensure that the benefits of dredging outweigh the costs.

As an example, the City of Calgary commissioned an independent report on the merits of dredging the Glenmore Reservoir. The report concluded that the increased capacity that could be gained by dredging would be small and would provide a maximum two percent reduction in moderate flood events (one in fifty year events, or 1:50) and less for larger events. The report also concluded that dredging the reservoir would disturb sediment that could impact the quality of the city’s drinking water, would require transport and disposal of the dredged material and would have to be undertaken regularly as the benefits of dredging are temporary [4].

After the 2013 floods in southern Alberta, some reservoir maintenance options for flood mitigation were considered. Some of the flood mitigation options from Alberta WaterSMART’s “Bow Basin Flood Mitigation and Watershed Management” report included reservoir operational and infrastructure changes as well as reservoir maintenance.

The report also considered assessing the value of dredging TransAlta reservoirs (such as Ghost Lake). It is important to consider whether lost storage capacity in TransAlta reservoirs could be regained by dredging the reservoirs to remove the sediment and aggregate that has accumulated over many years. Dredging was suggested by some stakeholders as a more cost-effective means of gaining storage in the headwaters when compared to raising existing structures or building new structures [5].

Ghost Reservoir was presented as a specific example where dredging should be investigated. TransAlta indicated its position that dredging Ghost Reservoir would regain little capacity in terms of live storage. In addition, the City of Calgary determined that dredging Glenmore Reservoir for flood mitigation would have negligible benefits [6].

If a reservoir is built in an area where silt is expected to accumulate quickly, gates will be installed at the bottom of the dam. Periodically, operators can open the gates to release the sediment load downstream so that it goes back into the river system. Replenishing the sediment to the floodplain allows for healthy riparian zones and a resilient watershed. Silt that enters the floodplain acts as a fresh layer of topsoil with all of the nutrients required to sustain aquatic plants.

Reservoirs and dams can be removed for several reasons. In some cases, reservoirs may be removed because sediment has filled the reservoir, rendering it useless to its original purpose. Reservoirs may also be removed if they are deemed unsafe. For example, a dam on 40 Mile Creek in Banff National Park was found to be unsafe because of the risk of an earthquake damaging the structure, and subsequently causing flooding in Banff [7]. The dam was demolished in the summer of 2014 [8].

Removing a dam and reservoir can be very expensive, so this is not something that is done often. In addition, the environmental impacts of introducing a large load of sediment back into the river must be considered when planning to remove a dam. Introducing a large amount of sediment into the river can be deadly to fish. However, the long-term ecological benefits of removing a dam may outweigh the negative impacts. For example, when a dam is removed, the river can return to its natural flow and fish can travel freely, which promotes spawning.

The Condit Dam, in Washington State USA, is an example of a dam that was removed recently. The dam had been on the White Salmon River for nearly 100 years until it was demolished in 2011. Click here to see a video of the Condit Dam’s removal.

[1] IAHS/ICWRS Project Team. (1998). Sustainable Reservoir Development and Management. Retrieved from: http://books.google.ca/books?id=AOKBbZoNXaYC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

[2] Hollingshead, A.B., Yaremko, E.K., and Neill C.R. (1972). Sedimentation in Glenmore Reservoir, Calgary, Alberta. Retrieved from: http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/pdf/10.1139/t73-009

[3] The Expert Management Panel on River Flood Mitigation. (2014). Calgary’s Flood Resilient Future.

[4] Expert Management Panel on River Flood Mitigation. (2014). Calgary’s Flood Resilient Future, p.37. Retrieved from: http://www.calgary.ca/_layouts/cocis/DirectDownload.aspx?target=http%3a%2f%2fwww.calgary.ca%2fUEP%2fWater%2fDocuments%2fWater-Documents%2fFlood-Panel-Documents%2fExpert-Management-Panel-Report-to-Council.PDF&noredirect=1&sf=1

[5] Alberta WaterSMART and AI-EES. (2014). Bow Basin Flood Mitigation and Watershed Management Project. Retrieved from: http://www.albertawatersmart.com/bow-basin-flood-mitigation-and-watershed-management-project.html

[6] City of Calgary. (2014). Calgary’s Flood Resilient Future: Report from the Expert Management Panel on River Flood Mitigation. Retrieved from: http://www.calgary.ca/_layouts/cocis/DirectDownload.aspx?target=http%3a//www.calgary.ca/UEP/Water/Documents/Water-Documents/Flood-Panel-Documents/Expert-Management-Panel-Report-to-Council.PDF&noredirect=1&sf=1

[7] Ellis, Cathy. (2013, December 12). “40 Mile Creek dam to be demolished.” Rocky Mountain Outlook. Retrieved from: http://www.rmoutlook.com/article/20131212/RMO0801/312129966/40-mile-creek-dam-to-be-demolished

[8] Ellis, Cathy. 2014, June 5. “Dam demolished on Forty Mile creek.” Rocky Mountain Outlook. Retrieved from: http://www.rmoutlook.com/article/20140605/RMO0801/306059976/-1/rmo08/dam-demolished-on-forty-mile-creek

We provide Canadian educational resources on water practices to promote conservation and sustainability. Our team crafts current and relevant content, while encouraging feedback and engagement.

The Canada WaterPortal is a registered charity, #807121876RR0001

We recognize and respect the sovereignty of the Indigenous Peoples and communities on whose land our work takes place.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved.