Alberta shares an international border with the U.S. State of Montana as well as the provincial borders with British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and the North West Territories. As water crosses these international and provincial/territorial borders, there are transboundary water agreements in place to protect Canada’s and Alberta’s water interests while encouraging cooperation with other jurisdictions.

The following is a description of the three main transboundary water agreements that affect Alberta; 1997 Mackenzie River Basin Transboundary Water Master Agreement, the 1969 Master Agreement on Apportionment with Saskatchewan, and the 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty.

On October 30, 1969, the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and the Government of Canada signed the Master Agreement on Apportionment (MAA) to share waters that flow eastward and across provincial boundaries. Prior to signing the MAA, the need for cooperative watershed management was recognized by each prairie province due to water quality and quantity issues.

As early as 1945, transboundary water issues were addressed by the Prairie Provinces Water Board (PPWB) that administered recommendations for sharing water across provincial boundaries. After the MAA was signed and ratified, the PPWB became responsible for managing the MAA, mediating concerns, and reporting issues. Essentially, the signatories of the Agreement and the PPWB agreed in the revised Charter of 2017 that the mission of the PPWB was to:

Schedule A of the MAA, the Alberta-Saskatchewan apportionment agreement, dictates how much of the annual natural flow of each shared water body Alberta is required to pass to Saskatchewan. Schedule B is the equivalent Saskatchewan-Manitoba agreement.

For more information on apportionment monitoring and how water allocations are calculated click here.

Loosely speaking, the upstream jurisdictions are required to pass roughly half of the natural flow to the downstream jurisdiction. However, there are complexities in the agreements’ language relating to total annual flow, minimum instantaneous flow, prior apportionments, and the water body in question.

While Alberta is obligated to pass a specified proportion of the natural flow to Saskatchewan, the actual proportion passed varies by water body and how dry conditions are. In wet years, Alberta passes far more than its obligation. Droughts make that minimum obligation much more significant and potentially challenging.

For example, the 2019-2020 PPWB Annual Report notes that the percent of “apportionable flow” passed to Saskatchewan by Alberta ranges from a high of 99% (Cold Lake) to a low of 71% (South Saskatchewan). In contrast, during the 2001 drought, Alberta delivered 56% of the natural flow to Saskatchewan.

After the implementation of this Agreement in 1969, water licenses in the region have remained junior to the amount apportioned between Alberta and Saskatchewan. Senior licenses in place before the Agreement are subject to negotiation with the Government of Alberta, especially in seasons of low flow.

Water bodies included in the Agreement are the Cold River, Beaver River, North Saskatchewan River, Battle River, Eyehill Creek, South Saskatchewan River, Boxelder Creek, Battle Creek, Middle Creek, and Lodge Creek. For each of these eastward-flowing water bodies, groundwater and surface water quality are monitored while the following rivers are subject to apportionment monitoring; Cold River, South Saskatchewan River, Battle Creek, Middle Creek, and Lodge Creek. By apportioning water between Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, there is a process by which each province can achieve their share of water.

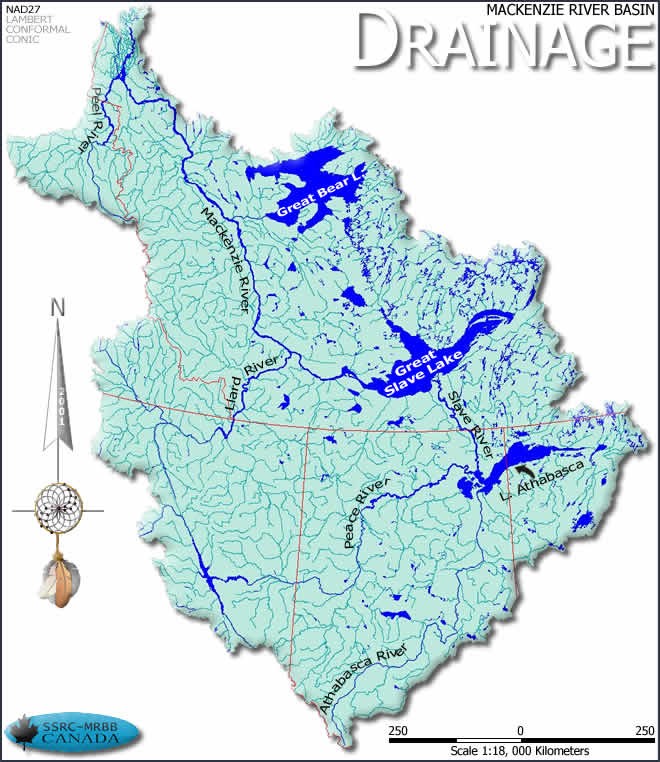

The Mackenzie River Basin is one of the largest watershed basins in Canada accounting for approximately 20% of the country’s land mass. Rivers in this basin begin as far south as the ice fields of Jasper and empty into the Beaufort Sea of the Arctic Ocean. The Mackenzie River Basin is shared between three provinces and two territories resulting in the joining of multiple regulatory and legal frameworks.

In July 1997, the Mackenzie River Basin Transboundary Waters Master Agreement was signed by the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, British Columbia, the North West Territories, the Yukon, and the Federal Government of Canada. The federal government acted as a facilitator between the parties and became an integral actor in the negotiations of this Agreement.

The Agreement is administered by the Mackenzie River Basin Board (MRBB) which has two voting members (a Crown representative and an Indigenous member) from each province and territory, and three voting members from the Federal Government.

The Transboundary Waters Master Agreement is a “master” agreement and each province and territory is responsible for negotiating subsidiary bilateral agreements with the neighbouring provinces or territories with which it shares Mackenzie Basin water. Not all of these bilateral agreements have been finalized and, as of March 2024, Alberta was still in the process of negotiating its bilateral agreements with British Columbia and Saskatchewan. The finalized bilateral agreements can be found on the MRBB website.

By involving the Federal Government in this Agreement, water monitoring in the Mackenzie Basin could be improved through provincial and national efforts. In signing this Agreement, each province committed to transboundary water management and specific cooperative measures for the protection of the overall watershed. To achieve cooperation between each province, the Agreement outlines four guiding principles;

Additionally, the Mackenzie River Basin Board was established to aid in the implementation of this Agreement while promoting each guiding principle.

Bilateral water management is when two jurisdictions cooperate in the management of a shared resource, such as water.

For more information click here.

Included in the Agreement is the requirement for neighbouring jurisdictions to develop bilateral water management agreements to address specific issues at particular jurisdictional boundaries. Once implemented, these agreements will provide regulations for water quality, quantity, and flow requirements.

In November 2014, the North West Territories and Alberta finalized their bilateral agreement negotiations. In this bilateral agreement, cooperative measures have been implemented to manage transboundary waters, protect shared ecosystems, and enforce information-sharing requirements for downstream developments.

Overall, each of the bilateral agreements in the Mackenzie River Basin will serve to address the different regulations and expectations of each Province/ Territory while promoting continued ecological integrity within the Basin.

In 1909, Canada and the U.S. signed the Boundary Waters Treaty to address transboundary water issues and disputes between the two countries. Specifically, issues of water quality and quantity required a framework for cooperation where both countries could benefit from a mutual understanding of water management. The International Joint Commission (IJC) was created in 1909 to facilitate disputes, negotiations and subsequent agreements within the scope of the Treaty.

Note that the Boundary Waters Treaty leaves Alberta (and the other affected provinces) in an interesting position. Under Canada’s natural resources arrangements, the regulation of water is a provincial/territorial responsibility. However, the Boundary Waters Treaty is a nation-nation treaty and so the provinces (and U.S. states) are not party to the agreement and are, therefore, essentially interested observers who implement the directives of the International Joint Commission.

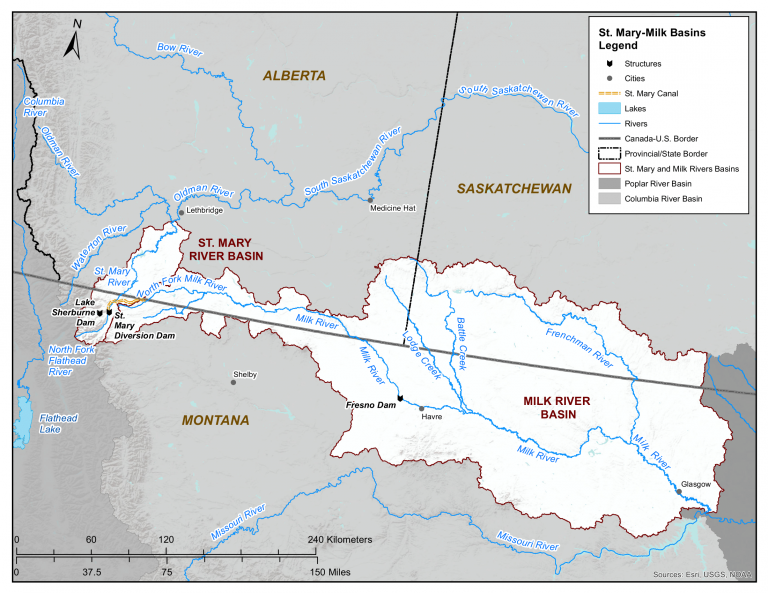

The Boundary Waters Treaty applies to both the Milk and St. Mary river basins in Southern Alberta. The Milk River flows into Alberta and exits to the U.S. State of Montana while the St. Mary River joins the Oldman River near Lethbridge, Alberta. The Treaty provides ground rules by which water is divided between Canada and the U.S. and negotiated between the federal governments. At first, issues such as a common definition for the amount of water allocation could not be agreed upon by the U.S. or Canada, prompting the IJC to conduct hearings between 1915 and 1921 to gather information that informed a decision on an acceptable and agreed-upon definition. Final rules established by the 1921 IJC Order interpreted the Treaty and provided annual operating rules for the measurement and entitlement to water volumes and flow rates. The Order reinforced prior appropriation and beneficial use as the system of rules for governing water management between Canada and the U.S. Currently, the 1909 Treaty addresses the irrigation season that occurs between April 1st and October 31st of every year, which requires careful water allocation between jurisdictions. In the St. Mary’s River basin, Canada is entitled to 75% of the first 666 cubic feet per second (cfs) of flow during irrigation season. Alternatively, for the Milk River basin, the U.S. is entitled to 75% of the first 666 cfs, while Canada receives 25%. In non-irrigation seasons, both the Milk and St. Mary’s Rivers flow are split evenly between Canada and the U.S.

In Alberta, the Boundary Waters Treaty has resulted in significant investments in methods of water storage and delivery for various water users. Alberta has built infrastructure to store and use water as needed within the Treaty’s requirements. Despite strict water allocations stipulated in the Treaty, both Canada and the U.S. cannot use their entire share of the rivers water due to variability in river flows during different seasons. To ensure there is an adequate supply of water for the environment, water allocations are determined as a percentage of the flow in a given season. This restricted use, in addition to other rules stipulated in the Treaty and Order, have resulted in a strong basis for Canada and the U.S. to work through annual operations.

Share this Post:

We provide Canadian educational resources on water practices to promote conservation and sustainability. Our team crafts current and relevant content, while encouraging feedback and engagement.

The Canada WaterPortal is a registered charity, #807121876RR0001

We recognize and respect the sovereignty of the Indigenous Peoples and communities on whose land our work takes place.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved.